by Brian Kunde

I’m going big on today’s de Camp highlight, since the book in question needs the attention. Solomon’s Stone (Avalon Books, New York, 1957) is the Cinderella of de Camp’s early fantasy novels, if you can imagine a Cinderella who never went to the ball, tried on the slipper, or married the prince. It’s on no one’s favorites list. It’s had no print editions in English since the initial hardcover. If ever de Camp novel was neglected, it’s this one.

Not that it started out that way. It had the customary christening of his early fantasies in the pages of Unknown Worlds (vol. 6, no. 1, June 1942), under the patronage of the usual fairy godmother, editor John W. Campbell, Jr. It reappeared in normal fashion in the pages of the British Unknown Worlds (vol. 4, no. 4, summer 1949), and thence passed, in due course, to the specialty publisher Avalon Books, responsible for bookifying a fair amount of the author’s periodical works, which brought it out in hardcover. And then … pretty much nothing, until the unavoidable Gateway e-book version (Gateway, London, May 26, 2016).

I say pretty much nothing because it wasn’t quite nothing. There were two translations nestled in between the Avalon and the Gateway. The first was Italian, translated by Gianni Samaja as La gemma di Salomone for I Romanzi del Cosmo #78, giugno1961. It shared the issue with two serial installments of other stories, part three of three of “Il mondo che noi cerchiamo” by “John Rainbell” (Roberta Rambelli), and part one of six of “Gli eredi del cielo” by “Hugh Maylon” (Ugo Malaguti); both being Italian stories by Italian authors writing under English pseudonyms. One gets the impression that English and American SF were more prestigious in Italy than native efforts at the time.

The Samaja translation of Solomon’s Stone was popular enough to rate a second appearance, in Cosmo: I Capolavori della fantascienza #48, dicembre 1964, this time paired with Le dimensioni dell’odio by “Morris W. Marble” (Manrico Viti) and various other pieces, including a couple more stories by Rambelli and Malaguti. The Viti novel had also originally appeared in I Romanzi del Cosmo (#77, the issue before Solomon’s Stone). This reprint of the Italian version is virtually unknown to bibliographers. Laughlin and Levack don’t record it, and neither does the usually comprehensive Internet Speculative Fiction database. It’s in the Catalogo Vegetti della Letteratura fantastica, though. (see https://www.fantascienza.com/catalogo/volumi/NILF119480/le-dimensioni-dell-odio-la-gemma-di-salomone/)

The second foreign version, much later, was German, translated as Der Stein der Weisen: roman by Peter Robert (Ullstein, Frankfurt-am-Main, 1987. Ullstein didn’t relegate it to appearance in a periodical, but made a proper book of it.

And that really is it. Seven appearances, four in English, two in Italian, one in German; four of them in magazines (one American, one British, two Italian); two of them as print books (one American, one German); one as an e-book (British). It didn’t even rate an American paperback, leaving the Avalon hardcover the only version for your shelf if you want it as an English language book. This is, to say the least, unusual. How did this novel get orphaned?

We’ll get to that, but first let’s look into the covers.

The initial magazine appearances need not long detain us. Solomon’s Stone is the featured story among the four tales that make the cover of the American Unknown Worlds. Unfortunately, that just means it rates more text space; the other three also get pictorial vignettes. It does get seven interior illustrations by Frank Kramer, at least. The de Camp novel is also the featured story on the British Unknown Worlds cover, though here it does get its own vignette, of the protagonist, Prosper Nash, in his cavalier persona. Nice, but uninvolving. There are no artist credits for any of the vignettes.

The Avalon hardcover is better. Ric Binkley provides full color imagery for the dust cover’s front and spine; the former has a small portrait of Nash at the upper left on a field of stars, triangularly connected by lines to the titular stone of Solomon (center right) and planet Earth (lower right); a subsidiary full figure outline (in red) of Nash’s cavalier identity (left half of the painting) is similarly connected to the stone and the Earth by similar dotted lines emanating from an outstretched hand. The stone, inscribed with Hebrew letters and a prominent Star of David, is the focal point of the cover, backlit by pink and blue flames; wavelike blue lines emanate from it. The spine repeats the image of the stone in its bed of flames, superimposed over the Earth. Overall, the composition is intriguing and evocative of the story, without presenting any particular scene from the story. Still, it does makes one want to read it. As for the rest of the dustcover, the front and back flaps blurb the story and note the author is “one of the modern masters of imaginative fiction,” while the back cover blurbs an unrelated Avalon publication, Manly Wade Wellman’s Twice in Time.

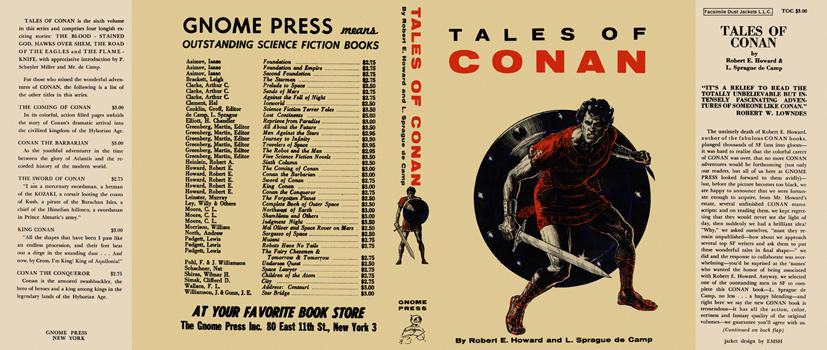

Cover artist Ric Binkley (working name of Richard Roland Binkley, Jr. (1921-1968)) was a little-known but important figure in the mid-twentieth century speculative fiction book boom. He was active in providing cover art for Fantasy Press, Gnome Press, and Avalon Books for several years from 1950 onwards before dropping into obscurity. His work is varied and credited with “rare flashes of odd creativity,” but considered undistinguished and often derivative. He is remembered primarily “because he painted the first covers for many books now regarded as classics.” (Gary Westfahl, profile of Binkley in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/binkley_ric)) But he was certainly capable of getting the job done, as shown above.

Moving on to the remaining covers, the Italian magazines give us dramatic but generic space scenes, unrelated to the content of the issues, while the German book version spoofs us with a dramatic David B. Mattingly painting originally made for the Barbara Hambly fantasy novel The Armies of Daylight (Del Rey/Ballantine, 1983). It’s a good painting, but has nothing whatsoever to do with Solomon’s Stone. As for the Gateway, it’s the customary travesty; publisher, blurb, title and author in black or red print on a field of stark yellow. I appreciate Gateway for keeping much of de Camp’s work available to readers (in other countries, at least, if not the U.S.), that otherwise would not be. But its covers are crap.

Except … lately, Gateway has been redoing some of the covers of its ebooks pictorially. There seems little rhyme or reason as to which they select, though in the case of de Camp, it’s mostly some of his more popular works. Lest Darkness Fall. Rogue Queen. Lovecraft: A Biography. The Pratt collaborations The Incomplete Enchanter, The Castle of Iron, Wall of Serpents, and Land of Unreason. And, lately, inexplicably, Solomon’s Stone. Which is … not one of de Camp’s more popular works. The few new covers do, I suppose, outclass those yellow things still fronting most Gateway offerings, though, alas, still largely crap.

The new Solomon’s Stone cover has cavalier Nash descending, sword ready, a stone staircase into a murky cavern, his way lit by a lantern held in his other hand. (His right; I don’t recall if he’s left-handed in the text, but he certainly is on this cover.) His cavalier outfit is reasonably authentic, but oddly furry. The overall color scheme is black, white and grey, with red highlights on his outfit and bright yellow light from the lantern, giving a slight beige cast to the cavern walls. A translucent red banner bound above and below with thin yellow stripes obscures much of the cover’s lower half, on which the author’s name appears in large white capital letters with the title beneath in ordinary yellow italics. It’s actually one of Gateway’s better pictorial covers, but still, as a scene, rather drab. A for effort, C for composition.

Which may point us to one reason for the obscurity of this novel; it is not well served by its presentation. Avalon and Ullstein provide adequate art, but only the former draws you into the story. (The latter, I suppose, might draw you into the Hambly story, had Ullstein not done its bait-and-switch.) None of the others really sell the work, or, in most instances, even address it. Still, other de Camp novels have survived bad art. Heck, most of them have.

Perhaps the critical response had something to do with it? Reviews of Solomon’s Stone came in two main phases; responses to the Avalon publication (late 50s-early 60s), and mid-to-late career surveys of de Camp as an author (mid-70s and sporadically after). You can locate much of the former in the Internet Speculative Fiction database, and find it handily quoted (by me, actually) in the Wikipedia article for the book. The consensus is epitomized by P. Schuyler Miller; “slight, but fun.” (Astounding Science-Fiction, vol. LXI, no. 3, May 1958, page 147) Not exactly a ringing endorsement. Floyd C. Gale, more ominously, was disappointed, feeling it “remov[ed] some of the gilt from an idol” who “has done better in the past with less.” (Galaxy Science Fiction, vol. 16, no. 3, July 1958, pages 108–109)

Later commenters have run the gamut from Brian M. Stableford, who deemed it “perhaps the best” of de Camp’s early solo fantasies, (Supernatural Fiction Writers, 1985, v. 2, page 927) to Don D’Ammassa, who found it “barely readable.” (Encyclopedia of Fantasy and Horror Fiction, New York: Facts on File, ©2006, page 81) But … so what? The early mixed reviews did not stop other de Camp novels from getting reissued, and the late ones came in the midst of what was already a Solomon’s Stone vacuum. For the record, I disagree with D’Ammassa; the book is eminently readable.

I had no access to any of these as a de Camp-seeking teen in the 70s. More relevant to me was Lin Carter’s survey of the master’s fiction in Imaginary Worlds (Ballantine, New York, June 1973). On pages 81-82 he briefly discusses two of the early fantasies, The Undesired Princess and Solomon’s Stone, neither then in print since the 50s. Carter does not pass judgment, and makes more of what de Camp did in those books, with his rational approach to fantasy, than he does of their stories and plots. Nevertheless, he whets the appetite; I yearned to read those books from then until the late eighties, when I went to work in a library that had both, and could. The Undesired Princess was subsequently brought back to print in 1990. Solomon’s Stone… well, I’m still waiting. I finally got my own copy (of the original Avalon edition) just this year. In fairness, de Camp’s solo fiction in general was hard to find when Carter wrote. A good part of my obsession with it stems from it being so damned unavailable back then. The later 70s onward were better times for the de Camp fan, thankfully.

Lin Carter himself had something to do with those better times, by enthusiastically restoring to print a few early de Camp and Pratt titles in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series (Pratt’s The Blue Star (May 1969), de Camp and Pratt’s Land of Unreason (January 1970) and “The Wall of Serpents” (in Great Short Novels of Adult Fantasy I (September 1972)) and showcasing newer de Camp tales in his Flashing Swords! and Best Fantasy of the Year anthology series. Had the Ballantine series lasted longer, the Carter-de Camp friendship continued unstrained, or Carter’s personal and professional lives not spiraled into the abyss they did, he would doubtlessly have given us more.

Maybe … copyright issues? Some 50s small publishers managed to tie up rights to the works of the authors they published, complicating their reissue later on—notably Gnome Press, whose bankruptcy caused headaches not only for de Camp, but Isaac Asimov and Robert A. Heinlein, among others. That doesn’t seem to have been the problem here, though. Solomon’s Stone was initially copyrighted by Street & Smith Publications on publication in Unknown Worlds; the Avalon edition is copyrighted by Thomas Bouregy & Company (the actual firm behind the imprint), but that applied only to that edition, not the original text. In any case, copyright was renewed in 1969 by the author himself, and from that point onward, if not before, anyone who wanted to reissue the book could have done so, given his permission. So either no one was interested in doing so, or he wasn’t.

Was he himself ambivalent about the work, then? What if he took those old mixed reviews to heart, and decided it wouldn’t do his reputation any good, even if it managed to make money. What if he was soured by his experience with paperback publishers in the 50s and 60s, who had either altered his titles and texts (Ace, with The Queen of Zamba), or gone belly-up, leading to more issues with copyright reversion (Lancer, with the Pratt collaborations and the Conan project). What if he was just too focused on current projects.

Doubtful. The course of his career from the late 40s to the mid 60s indicates he was up for anything that might sell (historical novels, science articles, children’s nonfiction), and a fair amount that wouldn’t (Round About the Cauldron, the nonstarter later salvaged as Spirits, Stars, and Spells).

Most likely, then, there was no interest from editors or publishers. If they wanted anything from his early career, it was Lest Darkness Fall and the Pratt collaborations—works with proven popularity and/or track records. The rest? Well, as de Camp’s star rose again through the 70s and 80s, those tended to come back as well, if slowly and fitfully. Not everything, of course; some titles were overlooked. Still, on the strength of de Camp’s newer work, fresh publishers such as Tor and Baen proved willing to mine the de Camp backlist in the 80s and 90s. Maybe it didn’t meet expectations. Maybe he even died too soon. Nothing kills interest in an author’s backlist like the prospect of there being nothing new from that author.

Solomon’s Stone, old and obscure, likely just fell through the cracks, reaping the consequences of early neglect with continued neglect, until too late. These days, when we’re grateful just to have de Camp’s major works available. Few tears are shed for the minor ones.

But let us not end on that note. This is, after all, an actual novel, with actual content. It has characters. It has a plot. It tells a story. Things happen. Almost none of which I’ve done more than touch on, so far. So what’s in the book? Regardless of why no one has sufficiently cared about it over the years, what does it offer for us to care about?

Glad you asked! Or I, on your behalf. Solomon’s Stone is vintage de Camp! (Indeed, his vintages doesn’t go back much further.) It presents us with an ordinary guy, cast into a crazy new world of self-projection and wish-fulfillment, and extraordinary, even fantastical, circumstances, from which he struggles manfully to extricate himself. He is beset by slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, most unfair, many harmful, some just humorous. Indeed, they come so thick and high his success appears not merely doubtful, but impossible. He is both aided and hindered by coincidence, which breaks his way less often than you would expect for any self-respecting protagonist. (De Camp was no follower of Dickensian or Burroughsian plot strategies.) He changes. He finds himself fighting for more than merely his own goal (getting home), but the fate of his whole new world. Against all odds, he achieves both, only to lose what has become most important to him, which is—could it be? Yes! Love! As the curtain falls, he dedicates himself to returning to the strange new world of his exile, and recovering his lost love. (Yes, this is another early work with a sequel hook—destined to unfulfillment, as with The Carnelian Cube, that other early work with a stone nick-nack as MacGuffin.) Really, what’s not to love?

Well, for me, it was that growing pile of insurmountable odds, overstuffing the plot and daunting its resolution. Resolution does happen; Prosper Nash is almost literally saved by the cavalry at the end, a decidedly strange cavalry, to be sure, but one for which the groundwork has been carefully laid. But despite the prep work, it all comes across as one of those rare coincidences that do break Nash’s way, since so many things had to go just right for it to happen—not that we mind it happening, but it does strain the willing suspension of disbelief, already stretched mighty thin by the very premise of the story.

That said, there’s much fun along the way. Things start out darkly, with accountant Prosper Nash attending an experiment in magic by friend and would-be magus Montague Allen Stark, who promises to summon a demon. It’s meant as a joke, with a confederate playing the infernal role to leap out at the critical moment. But the confederate is delayed, and the spell succeeds—the demon, one Bechard, is evoked. Moreover, Stark’s pentagram can’t contain Bechard’s type of demon. Bechard casts among the among the audience for one to possess—that is, in whose body to enjoy his newfound freedom, while the mundane soul of its rightful owner is displaced to the astral plane. Nash, striving to protect Stark, ends up as the victim—and with a quest, if he hopes to recover his body—to return within ten days with the Shamir, the titular stone of Solomon. If he fails, dire punishments are threatened.

The astral plane is the aforementioned world of self-projection and wish-fulfillment. There, people’s astral selves are as they dream of being—beautiful, rich, strong, heroic, whatever. Nash’s dream-self is Chevalier Jean-Prospère de Nêche, a dashing cavalier! He finds the astral version of his native New York City strangely transformed by the peculiarities of its inhabitants, some of whom are analogues of his friends back home. For instance, Bill Averoff, Stark’s confederate in the demon game, is here the rootin’, tootin’ cowboy Arizona Bill Averoff. Plain Jane Alice Woodson, an acquaintance, is here the gorgeous, desirable Alicia Dido Woodson. Play-acting magician Montague Stark is Merlin Ambrosius Stark, a true wizard. Shy bachelor Bob Lanby is Sultan Arslan Bey, owner of a magnificent harem—rather short its quota, women who dream of being concubines being scarce.

Bey’s dilemma is typical. The astral plane hosts numerous space patrolmen, but no space fleet, as few mundanes dream of being rocket mechanics. Its army consists almost solely of high officers, with only a single enlisted man (who, for logistical reasons, must therefore serve as its commander). Similarly magnificent absurdities abound. One the downside, this being the World War II era, the astral versions of numerous Italian and German citizens are idealized conquering Romans, fanatic anarchists, or Aryan supermen; the latter have organized themselves as Wotanists (or “Voties”), striving to subject the general populace. The Shamir, meanwhile proves particularly inaccessible, in the possession of its guardian Tukiphat on a fortified island. And Nash’s cavalier self has an unsavory history of being quick to pick a quarrel and careless of money and responsibilities. He thus finds himself pre-supplied with a host of foes nursing grudges. Getting settled into his new identity entails not just finding out who he is, but who has it in for him, complicating his bumbling efforts to secure the Shamir and even landing him in jail!

That’s his nadir, though. Released on the promise to enlist in the army, Nash gets down to business, running messages to the troops while rescuing the kidnapped Alicia and other prospective concubines from Arslan Bey’s harem, incidentally saving them from the Romans and Voties as well. Taking Alicia and (Merlin) Stark into his confidence and securing their aid, he even, finally, gains the Shamir. Society, however, is crumbling around them, the city reeling from an unsuccessful Anarchist revolt as the Voties prevail in the war. Captured, Nash passes the Shamir to Alicia so she can escape with it to the real world and contact the mundane version of Stark. He himself is condemned to death by the Voties, together with other companions. There is an amusing bit here about what order to execute them in; it’s decided it will be alphabetical, meaning Arslan Bey will go first—but should “de Nêche” be put under D or N? And what about the fellow who fellow who claims his name is Zwuggle; is he to be believed?

Rescue comes as the Voties are overrun by a host of monsters and heroes (led by one “Flash Rogers Stark”) dreamed up by Montague Stark in the real world, where Alicia has alerted him to Nash’s dilemma. Then Tukiphat shows up, demanding the Shamir. Nash tells him it’s in the real world, and why. The guardian is aghast, knowing Bechard could employ it in a wholesale demonic invasion of the mortal realm. Nash volunteers to help exorcise the demon; bodies are swapped again, and all is set right. Well, almost. Nash ends up back in his own body and on his own plane, but astral-Alicia must go back to hers to return the Shamir to Tukiphat. After an all-too-short reunion the lovers part, and Nash is left to go about repairing the damage done to his reputation by Bechard sojourn in his body. He discovers Montague Stark throwing away his books of magic, the whole misadventure having convinced him to forswear sorcery. Nash takes custody of the grimoires, hoping to employ them into somehow reuniting with Alicia.

The end. My assessment? A rollicking tale, a bit too busy and breakneck to count among de Camp’s best, but still, as almost everyone concedes, fun. It really deserved better. More editions. Bigger audience. But you get what you get. If you can get one, be sure to score yourself a copy!

As issued by Avalon, Solomon’s Stone bears no dedication, no introduction, no afterword, no author profile, no apparatus at all, save what appears on the end flaps. The text of the novel alone follows the title and copyright pages. Even in its original book form, it seems, this novel has suffered neglect!

#

(8/28, 9/7,9/2022)