by Brian Kunde

In my last highlight I profiled de Camp’s first general collection, The Wheels of If and Other Science-Fiction. This time I discuss the third, A Gun for Dinosaur and Other Imaginative Tales (Doubleday, Garden City, NY, 1963). The one between, previously highlighted was Sprague de Camp’s New Anthology of Science Fiction (not actually an anthology), in 1953. There were also a few single series collections in the interim. The next two general collections would be The Reluctant Shaman and Other Fantastic Tales in 1970, also previously reviewed here, and The Best of L. Sprague de Camp in 1978 (review forthcoming).

AGfD has a more extensive bibliographic history than its predecessors. The Doubleday hardcover first edition was issued simultaneously with one for its Science Fiction Book Club. A paperback followed from Curtis Books, New York, in 1969, and a British hardcover in “heavily coated pictorial boards,” rather than a dustcover, from Remploy, London, in 1974. The book had no less than two German offspring, being split into separate paperback volumes, each with half the content of the original. Ein Yankee bei Arisoteles (literal translation: A Yankee with Aristotle) and Neu-Arkadien (literal translation: New Arcadia), both from Heyne, Munich, in 1980. And … actually, that’s it. Nothing more recent. Some of the stories have been remixed into later collections, but there have been no new editions of this one, not even in audio or ebook. De Camp’s collections have not been as well served in that regard as have his novels.

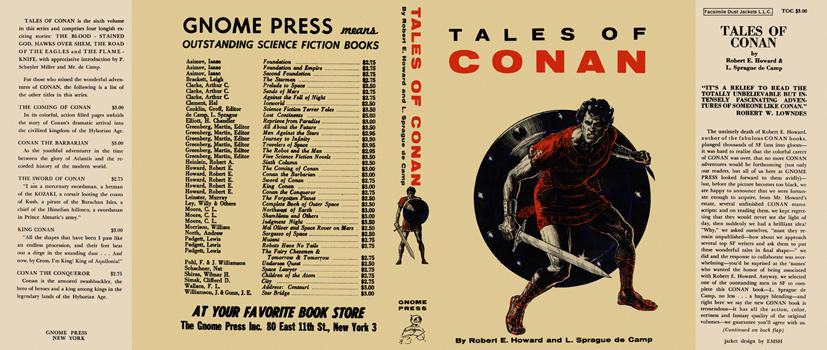

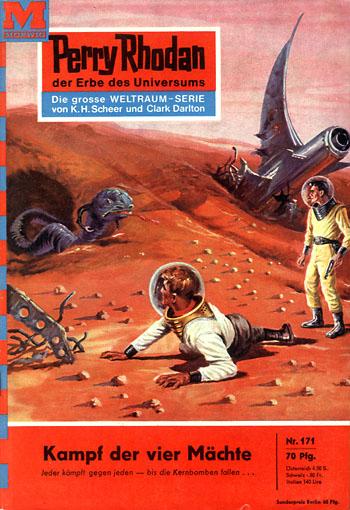

This collection has been ill-served by its covers, as well. The Doubleday volumes were adequate, featuring the silhouette of a dinosaur (duckbill, it looks like) atop an assemblage of gears and springs on a plain blue background. The Curtis and Remploy editions each went with boilerplate art having nothing to do with the content. The Curtis swiped its image from, I kid you not, a German Perry Rhodan issue, specifically #171, December 11, 1964! The art, by Johnny Bruck, features two astronauts whose spaceship has crash-landed on an alien desert planet; they are menaced by sort of blue centipede-lizard with arms and a big head emerging from a cave. Needless to say, the scene matches no de Camp story either in or out of this book. So, naturally, that’s the cover I scanned to accompany this review at the top (as opposed to just swiping images from the internet).

I sense your double-take, and your question. Why? Simply because, as with The Wheels of If and Other Science-Fiction, the present collection is more available and affordable in paperback than hardcover, and it’s the Curtis paperback that I happen to own. Sorry, but there it is. Enjoy, Perry Rhodan fans!

Moving on, the Remploy gives us an anonymous image used on many of its books, with, again, two astronauts in spacesuits advancing wide-eyed through an alien desert landscape. To the right of them, a greenish humanoid alien emerges from the ground, if “emerges” is even the word; it seems attached to the ground. In the sky behind the alien are no less than nine identical moons, seven of them seemingly attached to each other.

The Heyne covers are better. Matching the same publisher’s translation of The Wheels of If and Other Science Fiction, they give us the publisher’s device (“Heyne Bücher” in a ribbon over “Science Fiction Classics” in an oblong globe-like diagram), the title in yellow over a pictorial box in a red border, and the author’s name (as “Lyon Sprague de Camp”), also in yellow, at the bottom. In each instance, the pictorial element is by artist Karel Thole.

Ein Yankee bei Arisoteles shows a semi-recumbent, semi-transparent man (through whom we view a distant cityscape of skyscrapers) appearing before Greek philosopher Aristotle, wrapped in a period-correct himation (the reader will be forgiven for assuming it a Roman toga). The surroundings are rather abstract; black and hazy to the left and bottom, and polygons splitting away from each other to the right and the top. Obviously meant to represent time traveler Sherman Weaver meeting Aristotle in “Aristotle and the Gun,” though Aristotle was not in fact a witness to his materialization in that tale.

Neu-Arkadien, meanwhile, gives us a naked woman, seen from behind, beneath a tree, waving at a spacecraft descending from the sky on the other side of a river or strait. Here the story “New Arcadia” is represented. The spacecraft is the Daedalus, and the woman presumably female lead Adrienne Herz. Though she was not alone in greeting the spacecraft, which in the story was greeted by two feuding factions of the utopian colony of Nouvelle-Arcadie, of which only hers espoused nudity. Moreover, the story opens after the Daedalus has landed. Still, both covers are decent efforts.

It is interesting to compare A Gun for Dinosaur and Other Imaginative Tales with its predecessor, The Wheels of If and Other Science-Fiction. TWoI was a good sampler of de Camp’s pre-war short fiction. AGfD performs the same service for his post-war fiction. (So, in its way, did Sprague de Camp’s New Anthology. But the stories in AGfD are better.) Post-war, for de Camp, by and large means the 1950s. Between the war itself and de Camp’s difficulties getting back into fiction writing thereafter, the mid- to late-40s were mostly a wash for him.

So, how does 1950s de Camp look side-by-side with 1930s de Camp? Well, the earlier body of work was fresher and more innovative, while the later, to my eyes, shows more seasoning and maturity, and a leavening of the characteristic dry humor with a new seriousness. In some instances, his fiction takes a darker, even horrific, turn, that may lead some readers to wonder where the fun went. Oh, it’s still there. Just … not always. Some of these stories would not have been out of place had they been adapted to the E. C. Comics of the era. (Though they weren’t.)

Other contrasts. The settings, previously mostly earthbound, may now extend into interplanetary or interstellar space. The early protagonists, usually “good guys,” or at least reader-sympathetic, make room for more rogues and out-and-out baddies. In a contrasting trend, some have been domesticated—there are fewer single heroes and more family men. There is even an occasional leading lady in place of a leading man. Basically, our author has branched out. But he is still recognizably L. Sprague de Camp.

The author, or perhaps the editor, of the book, has divided and arranged the stories topically, as will follow. I rate this book somewhat superior to The Best of L. Sprague de Camp (1978) in that it collects all three of de Camp’s absolute best stories from the 50s, which I would contend are among his best, period. TBoLSdC only included two of them.

Trips in Time. These tales concern time travel, and, coincidentally, guns. The first assumes the immutability of the timestream, and the second the opposite, allowing for either the course of history being altered or branching it into parallel universes—the former, however, is implied. These are two of de Camp’s best three 50s stories. (“Aristotle and the Gun” is the one omitted from TBoLSC.)

• “A Gun for Dinosaur“ (Galaxy, March 1956). Time-traveling hunter Reginald Rivers recounts an anecdote from one of his time safari expeditions involving problematic clients. Courtney James is an arrogant and spoiled playboy; August Holtzinger is a small, timid man, too puny the handle the heavy weaponry needed to take down Cretaceous period dinosaurs. Reluctantly, Rivers allows him on the safari with a lighter caliber weapon. James’ reckless shooting rouses a slumbering Tyrannosaurus. Holtzinger tries to save him, but the creature shrugs off his gunfire and snaps him up. Rivers aborts the trip, angering James, who later tries to go back to the Cretaceous again and assassinate Rivers’ past self. But the space-time continuum has a rough way with time paradoxes… De Camp wrote this story in response to Ray Bradbury’s “A Sound of Thunder,” but what a response it is! It hardly languishes in the earlier tale’s shadow!

• “Aristotle and the Gun” (Astounding, February 1958). In a reminiscent letter written to an acquaintance in the alternate present to which he has been condemned, time researcher Sherman Weaver tells how, in his original timeline, he had reacted badly to the government shutting down his time travel project. Thinking to refashion his world in a more enlightened and advanced fashion, he uses his soon-to-be-mothballed technology to send himself back in time to ancient Macedon, where he hopes to change history by selling Aristotle on the wonders of science and the scientific method. Which goes so wrong. One amusing feature of the story is how it portrays Aristotle’s student, the young Alexander the Great, and his cronies (later his generals) as snotty, entitled juvenile delinquents—one of de Camp’s particular fixations in the 50s. In this collection, it also shows up in “Judgment Day,” “The Egg,” and “Let’s Have Fun.”

Gadgets and Projects. These are “gimmick” tales, of the sort favored by de Camp earlier in his career, often focusing on one peculiar innovation and tracing the implications of the same. These feel to me more nuanced, if perhaps less exuberant, than his early efforts.

• “The Guided Man“ (Startling Stories, October 1952). The Telagog Company can take over your body for you in awkward social situations, enabling you to negotiate them effortlessly. The service is a godsend for bashful Ovid Ross, until his controller decides he wants the same girl Ovid does… As I’ve noted elsewhere, this story might have worked well adapted to film as a screwball comedy. Which, alas, it wasn’t.

• “Internal Combustion” (Infinity Science Fiction, February 1956). De Camp’s only robot story. It gives a nod to Asimov’s classic laws of robotics, but the robots here are no positronic wonders, but gas-guzzling contraptions. It features a group of six worn-out models squatting as bums in an abandoned mansion, and the scheme of their leader Napoleon to take over mankind by training up a young human to become a puppet ruler. The Chosen One is a boy previously befriended by the hero, beach-combing robot Homer. Things go badly. The conspirators all perish in a gasoline-fueled house fire, but Homer manages to get his friend to safety before completely melting down. An oddly affecting, poignant tale, despite the absurd setup.

• “Cornzan the Mighty” (Future Science Fiction, December 1955). Television of the future is moving towards a process to program the actors into believing their performed adventures are real, thus enhancing verisimilitude. Trouble due to sabotage ensues on the set of Cornzan the Mighty, a planetary romance series de Camp makes a spoof of Tarzan, Conan, and Flash Gordon. Simultaneously! In spite of which, the story is quite effective; much better than the title and this aspect of the plot might imply. The recipe mixes together a hidden schemer, a scriptwriter smitten with the leading lady, a leading man confusing his character (and personal reality) with that of his previous role in Macbeth, a giant anaconda, and an inventor already envisioning the next advance in drama. Sprinkle in some life-threatening hijinks, pop into the oven, and bake until you have a full-blown disaster. Still, the right guy gets the girl! (Note: the “next advance” is a prescient vision of virtual reality.)

• “Throwback” (Astounding, March 1949). A discontinued scientific experiment to recreate ancient human species through back-breeding has left behind primitive giants segregated on reservations for their own protection. George Ethelbert, a specimen more intelligent than most, is recruited as a “ringer” to aid an ailing football team. He mops up the opposition so easily in his first game that the league bans his kind from the game. His recruiter, ruined, tries to renege on George’s contract and skip town, only to find the “primitive” cannier than he seems… This tale is a real romp!

• “Judgment Day” (Astounding, August 1955). The third of de Camp’s three best 50s stories. Physicist Wade Ormont discovers an unsuspected type of nuclear reaction that could make his reputation—and, in the wrong hands, lead inevitably to universal destruction. Should he publish his findings and bask in the ephemeral glory, or does the survival of a world that has rejected and despised him count more? (Caution: light-heartedness takes a complete hike in this one, it being de Camp’s primary contribution to horror fiction.)Quick aside, here. For any German readers, this is the point of division between the two volumes of Heyne’s German edition. The order of tales in that edition is the same as in the English version, aside from that of “A Gun for Dinosaur” and “Aristotle and the Gun,” which in the first volume of the German version are switched around. Onward.

Suburban Sketches. Here we find de Camp writing in his domestic vein, showing the effects of the extraordinary on the ordinary. All of which might be avoidable if someone displayed an ounce of responsibility!

• “Gratitude” (Galaxy, July 1955). Home gardeners of the future have more than one planet’s seeds to draw on. Suburban hobbyists Converse, Devore and Vanderhoff think they’ve found a windfall in contraband Venusian seeds. But the plants they produce are alarming; Devore’s singing shrub reproduces any sound impinging on it, while Vanderhoff’s bulldog bush bites whatever comes in reach. Worst of all is the tree-of-Eden nurtured by Converse, which ensnares victims through its enticing fruit and eventually leads them to sacrifice themselves to its needs. Yeah. There’s a reason these things are contraband. Is the neighborhood doomed, or will someone, Vanderhoff, maybe, rise to the occasion?

• “A Thing of Custom” (Fantastic Universe, January 1957). Milan and Louise Reid have been recruited to play host to a pair of Osmanians, happy-go-lucky, octopus-like aliens. A mining concession on their planet and the economic future of humanity depend on keeping them satisfied. Alas, the Reids find their new house guests selfish, spoiled, and demanding. The last straw comes when the Osmanians suggest swapping sex partners, as customary on Osman. The Reids are hardly keen on the idea—but perhaps their obnoxious but less inhibited neighbors, the Zeiglers, might prove more amenable? The next morning, in the cold light of day, the idea feels less than inspired to Milan, let alone government liaison officer, Rajendra Jaipal. They rush to the Zeiglers’, anticipating the worst. But they’re in for a surprise.

• “The Egg” (Satellite Science Fiction, October 1956). Reptilian alien ambassadors to Earth who are expecting a hatchling employ a local teen girl to watch their egg while they go out. Egg-sitting should be an easy job, but matters get complicated when Patrice’s boyfriend Terry, a would-be Lothario, comes over. Her mind on other things, Patrice fails to notice when the egg hatches early. And Yerethian young, it appears, are aggressive and ravenous just out of the egg. Luckily, the craven Terry isn’t Patrice’s only admirer…

• “Let’s Have Fun” (Science Fiction Quarterly, May 1957). Norman and Alice Riegel run a daycare for the young of various alien delegates during a conference attempting to establish an interstellar government. Alas, Earth is hardly a safe haven for such. Its permissive laws have resulted in its own young becoming irresponsible, entitled hoodlums who escape all consequence for their excesses, and a local gang of these delinquents have settled on the Riegel’s daycare as the perfect place to indulge in a bit of alien-bashing…

Far Places. Specifically, other planets, as earthbound settings give way to extrasolar ones. Though humanity, it would seem, is the same everywhere.

• “Impractical Joke” (Future Science Fiction, April 1956). An interstellar expedition should have no place for bullies, but spaceship pilot Harry Constant, with his vital skills, geta away with things others can’t. Even so, targeting Winthrop Fish, the sensitive expedition financer, as victim of his pranks takes things too far. Constant’s jests drive Fish to the brink of insanity, but he just can’t quit. His final scheme is to fake a swarming of the deadly naupredas native to the planet the expedition is studying, only to provoke an actual swarming—with fatal results. As always, Constant’s indispensability saves him, though his career is another matter.

• “In-Group” (Marvel Science Fiction, May 1952). Treasure hunter Ali Moyang rescues archaeologist Charles Bertin in the wilds of planet Kterem. To Ali, Bertin, with his local contacts, appears the key to locating valuable artifacts. Bertin is horrified at the prospective loss to science, but his rescuer holds all the cards. Or does he? It just so happens that Bertin knows a thing or two about the locals Ali doesn’t. Things that will make Ali realize, however briefly, that saving Bertin was a huge mistake… A dark, disturbing story. Ali’s our viewpoint guy, but we quickly come to sympathize with Bertin. Yet Bertin’s ideals leave little room for charity, or even, perhaps, humanity.

• “New Arcadia” (Future Science Fiction, August 1956). Journalist Gerald Fay travels to the planet Turania to report on the utopian Terran colony of Nouvelle-Arcadie, only to find it split by dissention, one faction having gone off to establish the rival settlement of Liberté. Looking into the dispute, Fay decides to visit each village in turn, starting with Liberté, with whose mail-girl, Adrienne Herz, he is smitten. The mystery deepens when she is abducted by aliens from Cimbria, ten light-years away, who, it ensues, have their own utopian colony on Turania. But Cimbria is the most peaceable world in the known cosmos—why would the Cimbrian colonists turn to violence? As it happens, there are utopias, and then there are utopias… (Note: the idea of interplanetary mail being microfilmed and physically transported between systems via spacecraft is one that recurs in the later Catherine de Camp story “The Horse Show”, appearing in her anthology Creatures of the Cosmos, from Westminster Press, Philadelphia, 1977.)

Final assessment for this collection? A strong, very strong sample of de Camp’s best fiction of its era, fully representative of what he was writing at the time. Oh, he wrote other good stories, as well as a few clinkers, some as fun as some of those here, and some as dark as others selected for the book. But ultimately, this one’s as good as it could be. While not containing all his top stories, I would rate it as his top collection.

A Gun for Dinosaur and Other Imaginative Tales bears the “Dedication: To Conway and Helen Zirkle.” Not very familiar names to the modern reader, however significant they may have been to de Camp. Who were they? A simple web search provides the answer.

Conway Zirkle (1895-1972) was a native Virginian, descended from German immigrant settlers in the Shenandoah Valley. Advancing through academia in Oklahoma, Virginia, Maryland, and Massachusetts, he ultimately became an associate and then a fully professor at the University of Pennsylvania, where he taught from 1950 until his retirement in 1965. Writing and publishing voluminously, he was an eminent botanist, biological scientist, and historian of science, and well-known as a fierce opponent of Lysenkoism. The coincidence of interests with de Camp should be obvious.

His wife, born Helen Emily Kingsbury (1898-1976) in San Francisco, California, was a graduate of Bryn Mawr College, where she achieved B.A. and M.A. degrees. She was a teacher at Brown Preparatory School in Philadelphia and a philatelist who wrote extensively on the stamps of Asia and stamp collecting in general. The Zirkles met at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, in the early 1920s, and married in London, England in 1923. Plainly, they were friends of the de Camps from the Pennsylvania years of both couples.

Your enthusiasm for Science Fiction Books is truly infectious! Your post highlights the genre’s capacity to push the boundaries of imagination and inspire new ways of thinking. Many thanks to spraguedecampfan for sharing such captivating insights!